Recovery from Parkinson’s

Recovery from Parkinson’s is provided for free download. Download PDF here: Recovery from Parkinson’s

What causes Parkinson’s disease?

Long term use of near-death mode

The norepinephrine override

A common example of turning off pause

Chapter 1: An Introduction

Chapter One: “A Curable Illness.” It begins: “Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease is not – and never has been – an incurable illness.” I saw my first Parkinson’s patient in 1996. I treated her for her foot problem, not her Parkinson’s disease. After all, everyone in the field of medicine knows that Parkinson’s is incurable. When she unexpectedly recovered, I logically assumed she had been misdiagnosed. When the next two recovered, questions began to fester. This book tells what happened after that.

More than twenty years have passed since those first patients recovered. I’ve worked closely with hundreds of Parkinson’s patients. Hundreds more have conferred or contributed observations via emails. Almost from the start, I was obsessed with seeking answers to the mystery of Parkinson’s disease.

I’ll start this book with the answers.

What causes Parkinson’s disease?

Parkinson’s disease is a collection of symptoms. These symptoms are set in motion by the long-term use of a highly specific, rarely used set of bio-electric circuits. Non-neural (not in the nerves) currents flow constantly throughout the body’s connective tissue and in the brain. The exact circuits used at any given instant depend on a person’s thoughts and biological needs at that instant. The particular circuit configuration that causes the symptoms of Parkinson’s should only run when a person is in near-death shock or coma. In people with Parkinson’s, the non-neural currents flow in the near-death circuitry all the time. In many people with Parkinson’s, their currents have been running this way since childhood.

In schools of Chinese medicine, the main pathways of the body’s non-neural currents are referred to as channels. The electricity flowing through all the pathways, great and small, is called “channel qi.” The word qi means “energy” and is pronounced chée-ee.

In this book, I sometimes refer to these currents as channel qi, sometimes as electrical currents. Feel free to call these currents whatever you want: electrical currents work the same way in English as they do in Chinese.

In a healthy person, these channels run in very specific patterns. When the channel flow becomes aberrant due to pathogens, injuries, toxins, and even subtle influences such as inclement weather or mood, the body might function poorly. Depending on the severity of the channel irregularities, health problems of corresponding severity can arise.

The flow of a patient’s channel qi can easily be detected by hand. Most students can begin to feel these electrical currents by hand after a few weeks of training. Detection of the these currents is objective, not based on intuitional whims or personal opinions.

At Five Branches, the acupuncture college in Santa Cruz, California, I teach a class in feeling channel qi. For students’ exams, they must correctly feel and write down for me the irregularities they detect, by hand, in a new patient’s channels. Students are usually happily surprised, early on in the semester, when they realize that they have each detected the same channel behaviors, in the same locations, on a given patient.1

Very early on in my Parkinson’s research, I noticed that the channel qi in people with Parkinson’s was always running backwards in one of the channels on the leg: the Stomach channel. I assumed, incorrectly, that this backwards flow of current was an aberration, held in place by an injury, in everyone with Parkinson’s.

Several years later, I noticed that other currents in my Parkinson’s patients were also behaving in a highly specific manner, a manner that conflicted with the healthy electrical patterns I had studied in school. Years passed before I learned that these electrical behaviors are related to the rarely used neurological mode that is only supposed to kick in when a person is on the verge of death or in a coma.

This near-death mode is not recognized in western medical theory, but it is in ancient Chinese medicine. The Chinese name for this neurological mode is “Cling to Life.” I have taken the liberty of giving it a more brisk and more biologically descriptive English name: “pause mode.”2

Early on, I observed that when the old, unhealed foot injuries of my first few Parkinson’s patients recovered in response to the supportive hands-on therapy that I was using, the channel qi began flowing in the correct direction and stayed that way. The symptoms of Parkinson’s ceased and never returned. This was before I knew about pause mode.

At that time, in the late 1990s, I naturally assumed that straightening out the aberrant channel qi by fixing the foot injury had gotten rid of the Parkinson’s symptoms. Therefore, this would be an effective treatment for everyone with Parkinson’s. I was wrong. My first few patients all had the same type of Parkinson’s disease – the type set in motion by an incompletely healed injury. I soon met people with Parkinson’s who did not respond to this type of therapy. I spent years working with hundreds of people with Parkinson’s before I eventually figured out that there are four different ways to get locked into this electrical flow pattern. Each of the four ways of getting stuck in this flow pattern requires a different method for getting unstuck.

Happily, no matter which system was used for setting pause mode in motion, when pause turns off, the body resets itself back to a healthy flow pattern. When the pause-mode type currents are turned off, Parkinson’s disease ceases.

Long term use of near-death mode

In healthy people, the near-death electrical pattern usually only kicks in for a very short duration. It can be triggered by excessive loss of blood, excessive perforation of the skin, concussion, or other near-death types of severe shock-inducing trauma or coma.

The symptoms of near-death trauma mode can include immobility due to inhibition of dopamine release for motor function, faint voice, lowered blood pressure, poor temperature regulation, inhibition of the swallow reflex, and even a sense of being outside the body – looking at oneself from outside the body – to name just a few. When attempting to come out of this mode, the body often exhibits tremor behaviors, also known as “shaking.” These symptoms are also characteristic of Parkinson’s disease.

The degree and type of immobility varies. In coma, a person is usually limp. In lesser degrees of pause, the body might manifest immobility with tension. Pause mode immobility with tension features automatic tightening up of certain muscles and relaxation of opposing muscles, leading to the body being curled into a somewhat fetal position.

As with the other neurological modes, all of the pause-mode physiology is activated and sustained via mode-specific electrical currents that run just under the skin and through the brain. Pause mode and the electrical circuitry associated with it are supposed to stop as soon as the body stabilizes and the risk of imminent death has ended. People with Parkinson’s have typically been using the circuitry of this mode for decades – often since childhood. They have been able to override the immobility-with-tension symptoms of pause mode by using a brain-based emergency override that will be discussed later in this chapter. The symptoms of Parkinson’s disease appear when a person stuck in pause mode can no longer summon up an adequate, self-convincing level of mental emergency, a level strong enough to fully activate the override.

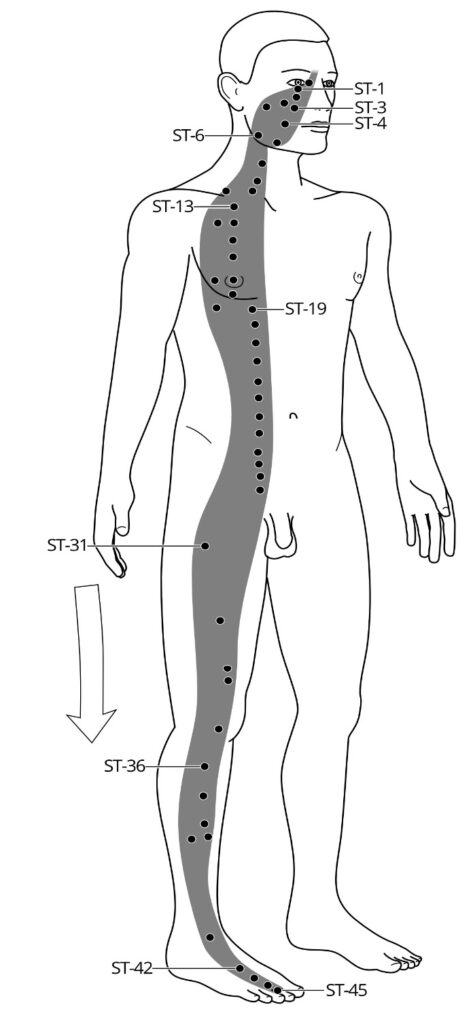

Fig. 1.1 The healthy, parasympathetic mode flow of the Stomach channel Please note: All of the Primary channels (channels named in honor of organs, such as the Stomach channel) have symmetrical left- and right-side paths. In this book, the artwork shows all the Primary channels on one side of the body only, for a less cluttered look.

Fig. 1.1 The healthy, parasympathetic mode flow of the Stomach channel Please note: All of the Primary channels (channels named in honor of organs, such as the Stomach channel) have symmetrical left- and right-side paths. In this book, the artwork shows all the Primary channels on one side of the body only, for a less cluttered look.

Four ways to get stuck on pause

The unhealthy, long-term use (stopping only during sleep – maybe) of pause mode can be activated in four different ways. The type of mental event or injury that triggered the long-term use of this mode determines which therapy needs to be used to turn it off. Two of the therapies involve altering some mental habits. Two of the therapies are physical and directed at old injuries. When, via these therapies, the electrical flow patterns of pause mode turn off, the currents automatically revert back to healthy flow patterns.

All of my hundreds of patients with Parkinson’s disease had used one or more of the four triggers that activate pause mode. People with Parkinson’s completely recover after using the appropriate method to successfully turn off the electrical currents typical of pause mode.

One of the channel qi alterations seen during pause mode – and in Parkinson’s

The following is a brief example of how one of the several pause-related circuitry shifts relates to symptoms of Parkinson’s. In Chinese medical theory, each of the twelve “Primary” channels that flow just under the skin is named in honor of one of the organs.

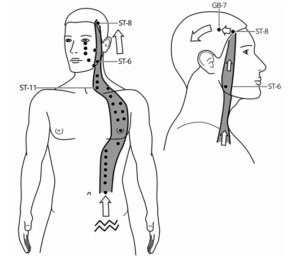

One of them, the Stomach channel, usually runs from the head to the toes. When pause mode is activated, the Stomach channel qi flows backwards, from acupoint ST-42 on the foot up to ST-6 on the jaw. Underlying muscles become rigid if the channel qi running over their surface is moving backwards.

In pause mode and in Parkinson’s, the span from ST-42 up to ST-6 is one of the body sections along which muscles become rigid, pulling the neck and front torso forward, causing the back to hunch, and tightening the muscles on the sides of the legs: part of the muscle behaviors that create the characteristic Parkinson’s posture.

When running backwards, the Stomach channel qi does not flow up to the center forehead. Instead, it flows from ST-6, on the jaw, up alongside the ear to ST-8, at the hairline, and then towards the back of the head. (See Fig. 1.2, page 5.) If the Stomach channel qi runs backwards all the way up to the jaw, no backwards channel qi traverses the face portion of the Stomach channel.

When the Stomach channel qi runs backwards, there is no channel qi flowing between ST-42, at the center of the foot, to ST-45, at the tip of the 2nd and 3rd toes. An absence of channel qi makes the underlying muscles become numb, cold, and/or limp. An absence of channel qi somewhere can allow the growth of fungus in the affected skin and nails at that spot.

In people with Parkinson’s, the absence of channel qi in the span from ST-1 to ST-6 on the face and from ST-42 to ST-45 on the foot causes the characteristic numbness and muscle limpness – not rigidity – that you might see in these areas.

The absence of channel qi on the face can contribute to the seborrhea (fungal growth in the skin) alongside the nose that is not uncommon in Parkinson’s. The absence of channel qi in the 2nd and 3rd toes contributes to the severe toenail fungus often seen in those toes, and sometimes in the first (the “big”) toe, in people with Parkinson’s.

In Parkinson’s disease, people develop specific areas of muscle rigidity and other specific areas of limp, numb, or atrophied muscles. These areas correspond perfectly to the areas in which channel qi either flows backwards or is absent, respectively, during pause mode.

Fig.1.2 During pause, Stomach channel qi flows backwards and up to ST-6. When the channel qi arrives at ST-6, it is shunted up to ST-8 and then flows into the Gallbladder channel. Compare the amount of energy flowing over the cheeks in Fig. 1.1 on the previous page and in Fig. 1.2 above. The absence of energy moving over the cheeks causes the expressionless “mask” face that can contribute to the characteristic look of Parkinson’s disease.

Fig.1.2 During pause, Stomach channel qi flows backwards and up to ST-6. When the channel qi arrives at ST-6, it is shunted up to ST-8 and then flows into the Gallbladder channel. Compare the amount of energy flowing over the cheeks in Fig. 1.1 on the previous page and in Fig. 1.2 above. The absence of energy moving over the cheeks causes the expressionless “mask” face that can contribute to the characteristic look of Parkinson’s disease.

When the electrical patterns of pause turn off, people recover from Parkinson’s. Parasympathetic mode flow of channel qi resumes. The rigid muscles become soft. The inactive or atrophied muscles slowly resume tone. When pause turns off, the toenail fungus and facial seborrhea, if any, very often clear up on their own over the course of six months to a year.

The above short section on the Stomach channel qi changes that occur during pause mode serves as the merest of introductions to the relevant Chinese channel theory and its relationship to PD that you’ll get in this book. Other channels that are altered during pause – alterations that explain other symptoms of PD – are introduced in later chapters.3

The norepinephrine override

In the decades before Parkinson’s symptoms appear, a person on pause is able to move around seemingly normally, or with even more strength and/or stamina than most people. How is this possible? This question takes us back to western medicine. When a person or animal is on a high degree of pause, his release of brain-based dopamine for motor function and his release of adrenaline from the adrenal glands, located next to the kidneys, are both highly inhibited. He is nearly motionless.

However, if an animal or person on pause is still conscious and needs to move for some reason of extreme emergency such as the injuring predator now moving towards the victim’s helpless offspring, the injured animal or person will be able to activate hyper-powerful emergency motor function. This motor function is very likely activated with norepinephrine.4

In nearly all of my PD patients, their symptoms began to appear when some life challenge that had long been consciously applied as a mental spur was finally laid to rest: the youngest child finished college; the mortgage was paid off; the predatory uncle died. With their fear motivator gone, they could no longer sustain a norepinephrine override strong enough to override the movement inhibitions of pause mode.

The reason their Parkinson’s symptoms appeared is not that their dopamine levels had dropped. We now know that people have more than enough dopamine at the time they are first diagnosed with Parkinson’s. The research supporting this statement is discussed in chapter three.

People with Parkinson’s haven’t used dopamine for motor function for decades – sometimes since childhood. When they recover, most of them are shocked and a bit giddy because of how utterly foreign it feels to use spontaneous (usually called “automatic”) dopamine-based movement as opposed to the conscious (you might say “word-based” or “mental command-based”), norepinephrine-driven movement that they have used for decades – ever since their sub-dermal electrical currents started flowing in the pause patterns.

For example, one recovered patient recalled how, at age seven, a classmate asked her how she was able to run so fast. She had replied, “I tell my arms to move back and forth as fast as they can, and the legs have to follow at that speed.”

Some forty years later, when she recovered from Parkinson’s, this habitually stoic woman told me how she burst into tears the first time her body used dopamine-based movement to get up from the sofa. Her tremor had already mostly stopped some days earlier. She was sitting on the sofa when she had the thought, “I should go into the kitchen,” and the next thing she knew she was standing up and moving towards the kitchen without having mentally instructed herself to stand up. Sobbing, overwhelmed with relief and self-pity, she had exclaimed to the empty living room, “Is this how easy it’s always been for everyone else?”

Based on patients’ amazed reactions to using dopamine after turning off pause, it seems very probable that most of my patients with Type I Parkinson’s have long used some alternative, non-dopamine neurotransmitter system for motor function. People with Type II and Type III Parkinson’s have usually not been as surprised by the sensations that arise when they resume using dopamine for motor function.

The four types of PD are detailed in the next chapter, but before discussing those four types we need to go through a bit more background and introduce some new vocabulary. In the early years of my research, I wrongly assumed the neurotransmitter that people used instead of dopamine was adrenaline. That assumption was based on my use of the western medical hypothesis that there are only two neurological modes. But during recovery, after turning off pause, some of my patients had to relearn how to activate their adrenal glands. The rush of adrenaline felt just as foreign (“Scary!” “Animal-like!”) as did the use of dopamine.

Based on research studies such as the one with mice that was footnoted on page 6, I hypothesize that the brain’s norepinephrine system is what my patients had been using for command-type motor function during all the years that they were stuck on pause. Based on what I’ve heard from my PD patients, norepinephrine, if that’s what they were using, enables a person to not only keep moving, but moving with abnormally heightened motor function. Many of my PD patients had been top athletes or ace pilots or captains of industry – roles that required an almost super-human ability to always be tireless, as well as stronger, smarter, and faster than everyone around them: emergency behavior. This doesn’t apply to all my patients, but certainly a large majority.

During the pre-Parkinson’s years, if a person who is stuck on pause can summon up a constant sense of emergency or intensity of purpose, he will be able to have what appears to be fairly normal or even superior motor function in spite of being on pause. However, this type of motor function is triggered by a mental-command process, a process very different from “automatic” or unself-conscious, dopamine-based movement.

Most healthy people are always using a blend of two types of movement: dopamine-driven and adrenaline/ norepinephrine-driven. At any given moment, the ratio of the blend depends on how relaxed or how uneasy they are.

I hypothesize, based on patient histories, that eventually, when the ability to concoct and sustain a mental sense of constant emergency diminishes, the ability to mentally activate the emergency norepinephrine override for pause also declines. That’s when the long-hidden, pause-like symptoms that we call Parkinson’s begin to manifest.

Adding to this hypothesis, people with Parkinson’s, even those who are nearly immobile with advanced Parkinson’s, can move perfectly normally during a true emergency. When fire is racing through the house, the vigorous norepinephrine override kicks in: emergency motor function is possible until the sense of emergency is over. (An exception: people who have brain damage from antiparkinson’s medications might not be able to move normally during an emergency.)

Dopamine is present in the brains of people with PD in high enough quantities until the PD becomes quite advanced. In fact, even in people with advanced Parkinson’s, dopamine levels are higher than normal in the right anterior cingulate part of the brain, an area used for risk-assessment, among other things. Dopamine use for motor function is inhibited during pause and during Parkinson’s. Dopamine use for risk assessment is increased during pause and during Parkinson’s.5

Clarification on the word “shock”

Some people refer to the near-death condition as “shock.” I don’t use the word shock much in this book because it has too many vague meanings. In the context of pause mode, the word “shock,” if used, does not refer to surprise, fear, or the type of “shock” associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. Post-traumatic stress disorder occurs when a person is stuck in sympathetic mode, also known as “fight or flight” mode.

The normal sequence of steps for turning off near-death mode

When an otherwise healthy person’s body has physically stabilized following a near-death trauma, when the likelihood of death is no longer imminent (meaning in the next few minutes), the body begins taking steps to turn off pause. When the interior, physiological functions of the body have stabilized, the body might begin to tremor, either visibly or internally.

A specific type of tremor can be a normal part of the process for coming out of pause mode. The tremoring performed while coming out of pause seems to serve as a query directed to the brain: “Hey brain! Internally, I’m on the verge of coming back to life! So tell me, is the coast clear?” or “Is it safe enough out there for me to come back to life?, to come out of the almost-paralysis of near-death trauma?”

The brain, using input from eyes, ears, smell, and touch, engages the risk assessment area of the brain to determine if the vicinity outside of the body is now safe, or at least safe enough to come out of the near-death mode.

When the interior of the body and the immediate vicinity outside of the body both seem stable and safe enough, the body will then perform three physical moves that turn off this mode and re-start the usual blend of the two more normal awake-time modes: sympathetic (fight or flight) and parasympathetic (curious and playful) modes. The moves include taking a slow, deep, audible breath, gently bobbling the head left and right at the very top of the neck, and then allowing a shimmy to travel down the spine.

Five steps in all.

The latter two moves restart the vagus nerves and spinal nerves, respectively. This reinstitutes the normal, waking-hours blend of parasympathetic and sympathetic mode channel qi circuitries, which then trigger the release of neurotransmitters, thought patterns, and cellular and organ behaviors appropriate for these modes. The person’s body resumes somatic awareness. “Somatic” refers to sensations inside the body, including awareness of being inside one’s body. The physiological behaviors of pause mode then cease.

This five-step sequence for turning off pause mode is not all that unusual. You might have seen a dog do it, after being badly startled. You might have done it yourself.

A common example of turning off pause

If you have ever found yourself shaking or trembling after a swim in an icy mountain lake (which triggers a blend of pause and sympathetic modes) or following on the heels of some intense, pause-inducing trauma, you might recall this sequence as you started to realize that you were warming back up or calming down, respectively. Your mind had an abrupt realization such as, “I don’t need to be shaking anymore,” and/or maybe “Hey, I’m gonna be OK, after all”: some thought synonymous with “I’m safe!” or “The coast is clear!”

This thought is followed by a deep, audible breath like a sigh of relief, a subtle head wobble, and a shimmy or shiver up or down the spine that almost feels like hitting an internal reset button. This sequence might be familiar to you…if you don’t have Parkinson’s.

Most of the people I’ve casually asked about this sequence do recall performing it in response to the brief tremoring or shaking that might follow a trauma, severe chill, or full-body anesthesia. But most of my Parkinson’s (PD) patients had no idea what I was talking about when I described the basic sequence for coming out of pause. Many even felt that it should be impossible for the brain ever to think that it’s safe enough to come out of pause, a mode characterized by wariness and heightened risk assessment.

As so many of my PD patients put it, “Only an idiot could ever think he was safe.” People with Parkinson’s, for various reasons, have become stuck in the electrical patterns of a neurological mode that can only be turned off when 1) the internal biological threat from the trauma has stabilized and 2) the person is willing and able to once again feel safe, or at least safe enough to turn off this mode.

My patients with Parkinson’s either:

a) had an unhealed injury (most often at the foot or head) causing pause-like electrical flow or

b) had told themselves to dissociate from a still unhealed injury or

c) had gotten stuck on pause following a severe trauma and never healed fully enough to come out of pause or

d) they gave themselves a pause-inducing command – often in childhood, often while staring into a mirror – a command something along the lines of “Feel no pain.”

The body does have a neurological mode in which it is numb to several kinds of physical and emotional pain: pause mode – the mode associated with near-death trauma and coma. When a person using great mental focus and grim determination commands himself to feel no pain, his brain might very well obey. It might shift into the near-death neurological mode of relative numbness…and stay there.

I refer to pause mode that is triggered in this fashion as “self-induced pause.” PD from self-induced pause is by far the most common of the four types of Parkinson’s disease, presenting in nearly ninety-five percent of my PD patients. I’ve named it Type I Parkinson’s disease.

Many people with Type I Parkinson’s do recall giving themselves some such command. Many who do not recall doing this nevertheless say that they embrace numbness, or something like “going into a dead place inside,” or “a grey place” as their way of dealing with unpleasantness or negative emotions.

Type I Parkinson’s has behavioral patterns not seen in the other types of PD. So even if a person with Type I PD doesn’t recall any sort of self-instruction, this type is fairly easy to distinguish. This book has instructions for diagnosing the four types. Whether or not a person remembers instructing himself to become numb or some other command that inadvertently induced pause mode, if this command is in place, the person will not be able to terminate the use of this mode until he changes some pause-related mental habits.

Again: in addition to Type I PD self-activation of pause mode, there are three other far less commonly used activation methods that can inadvertently lead to getting stuck with pause-like electrical patterns. As mentioned earlier, there are four ways to get stuck in the electrical patterns of near-death mode, and four ways to turn them off. So if you or a loved one have been diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease and are not taking dopamine-enhancing medications, be of good cheer. It is not an incurable illness.

Addendum to Chapter One

Please note: Before going any further, I want to make clear two things:

First, drug-induced and toxin-induced parkinsonism is not the same thing as Parkinson’s disease. These two parkinsonism conditions have some symptoms in common with idiopathic Parkinson’s, but they are recognized as being completely different disorders with different underlying causes. In cases of drug- or toxin-induced parkinsonism, the symptoms are the result of physical damage to brain cells. The treatments described in this book are not effective against drug- or toxin-induced parkinsonism. You will learn how to diagnose these “ism” syndromes in chapter fifteen.

Some MDs, if uncertain of a patient’s diagnosis because the symptoms are still mild, will diagnose the patient as having “parkinsonism” rather than giving the more alarming but more accurate diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. This is a shame, because the incorrect diagnosis might cause a person with early-stage PD to delay treatment. The sooner a person with Parkinson’s begins working on turning off pause, the easier it is. For the most common type of Parkinson’s disease, Type I PD, the wary thought patterns triggered by the unceasing use of pause mode steadily increase. This in turn, fortifies the other mental behaviors that sustain pause and can make it increasingly harder to turn it off. This also contributes to the steady worsening of the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. The sooner the treatment begins, the easier it is to recover.

This book will explain how to make an earlier and far more accurate diagnosis for Parkinson’s disease than is currently taught in western medical schools. Also, Parkinson’s disease is sometimes called “idiopathic Parkinson’s disease.” The two names mean the same thing. The word “idiopathic” means “cause unknown.” Second, modalities of Chinese medicine such as acupuncture, Chinese herbs, and moxa (smoking mugwort leaves) are not used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. I’ll discuss this more, later, but I want to mention this nice and early, before you rush off in search of the nearest acupuncturist in response to my references to Chinese medicine.

Your acupuncturist probably won’t know anything about pause mode. We do not learn about pause mode in schools of Chinese medicine. More than ten years into my Parkinson’s research, I stumbled across this neurological mode in an English translation of one of the most important ancient tomes of Chinese medical theory, the Huang Ti Nei Jing.

The only reason I understood immediately what the garbled language was discussing was that it answered so many of the questions I had accumulated in my years of researching Parkinson’s. I had acquired a lot of questions.6

Not only are the modalities of Chinese medicine not helpful in treating Parkinson’s, professional help of any type is usually not necessary. Acupuncture treatments by someone unclear on channel theory can accelerate the worsening of Parkinson’s symptoms. Acupuncture treatments might temporarily calm the tremor, but over the course of months, the symptoms will worsen faster than the symptoms of a person with PD who does not receive acupuncture treatment.

This was the finding of Dr. Ming Qing Zhu, the late, very famous Chinese neurology-specialist acupuncturist who developed the art of scalp acupuncture – with whom I once shared an office when he worked, briefly, in the late 1990s, in affiliation with Five Branches college of traditional Chinese medicine in Santa Cruz, California. For decades, in China, he had worked with hundreds of people with Parkinson’s, and found that those who received acupuncture treatments experienced temporary relief and, over time, faster worsening of symptoms than those who simply let the syndrome follow its natural course.

In China, most people cannot afford to take antiparkinson’s medications. This allowed Dr. Zhu to observe the natural progression of Parkinson’s in people who weren’t taking dopamine-enhancing drugs – something most American doctors never get a chance to see. After seeing the results that my patients were getting, he stopped working with people with Parkinson’s and referred them to the clinic that I conducted up until 2003.

The following paragraph is intended for practitioners of Chinese medicine. It’s included for that majority of acupuncturists who have not received much training in channel theory. Everyone else can skip the following paragraph.

Using the terminology of Chinese medicine, pause mode is an Excess condition. We never Tonify (strengthen) an Excess condition. Acupoints that purportedly “drain an Excess” do not actually reduce the amount of channel qi in the system, they merely break up some electrical blockage or area of high electrical resistance allowing for the dispersal of accumulated of channel qi, allowing the channel qi to resume flowing in its correct path. In the case of a person on pause mode, the insertion of needles will help the channel qi move better in its backwards direction – increasing the electrical signals of pause mode. Please don’t do this.

Do It Yourself Treatment

If you have Parkinson’s disease, please don’t rush out to find an acupuncturist. Or a therapist. Recovering from Parkinson’s is pretty much a do-it-yourself or a do-it-with-a-friend project. The book Recovery from Parkinson’s will explain how to do it.

Recovery from Parkinson’s is available for free download on this website. Click on Publications, then click on Recovery from Parkinson’s. The book is also available in hard copy at JaniceHadlock.com

The right to download and print out the books for individual use has been generously donated to the Parkinson’s Recovery Project by the author. All of the materials on this website are copyrighted and cannot be shared, copied, sold, or reproduced other than printing for individual use without the permission of the author. Contact her at [email protected].

1. I wrote a textbook for the class: Tracking the Dragon. The textbook can be used as a learn-on-your-own course by anyone wanting to learn how to feel the currents in the sub-dermal connective tissues. The book is addressed to the general public and does not presume any medical background. The chapters with instructions on how to feel channel qi and the appendix with the maps of the channels are available for free download at www.PDrecovery.org, the website of the non-profit Parkinson’s Recovery Project. Click on Publications, then click on Tracking the Dragon.

2. Ancient Chinese medical theory recognized four neurological modes: sympathetic (fight or flight) and parasympathetic (hungry, happy, and curious) and modes that drive behaviors of sleep and of near-death. Western medicine still only recognizes two, and those two only relatively recently, in the last two hundred-plus years. In chapter thirteen of the ancient Chinese medical text Huang Ti Nei Jing, pause mode is called “Close to Life” and, in other translations, “Cling to Life.”– From the Su Wen portion of the Nei Jing, chapter 13-9, from A Complete Translation of the Yellow Emperor’s Classics of Internal Medicine and the Difficult Classic; Henry C. Lu, PhD; published by the International College of Traditional Chinese Medicine; Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2004; p. 116.

3. New information is just starting to pour in from western medicine researchers on the subject of channel qi, or as they call it, “non-neural bioelectricity.” “Non-neural” means not related to nerves or neurons. A major researcher in the field, Dr. Michael Levin, professor at Tufts University and a visiting scholar at Harvard, has released on the internet an excellent video on his findings. He has bachelor’s degrees in computer science and biology, a PhD in cell biology, and is a licensed acupuncturist. He refers to this non-neural bioelectricity, what the Chinese call “channel qi,” as “the software of life.” He explains that we can manipulate this physiological software layer. He defines this non-neural bioelectricity as “slow, steady ion fluxes, electric fields, and voltage gradients generated and sensed by all cell types.”

He goes on to explain, “This is not the rapid action potentials in classical excitable cells [nerve cells] nor effects of environmental electromagnetic exposure.” He also says, “People might say that the cells are the hardware and the DNA is the software. But actually, the DNA only specifies the types of hardware, the types of components you might have. Bioelectric decision making [which components the DNA makes and how your cells use them] runs on the real-time physics [of bioelectric influences]…He also mentions, “All these electrical processes disappear when the cell [or the animal] dies.” This answers questions raised by the many western researchers who have failed to find evidence of channel qi in their cadaver explorations.

4. “Norepinephrine loss produces more profound motor deficits than MPTP treatment in mice”; K.S. Rommelfanger, G.L. Edwards, K.G. Freeman, et al; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America; 2007 Aug 21; 104(34):13804-13809. Published online: 2007 Aug 16. Doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702753104.

In this study, mice brains’ dopamine receptors were chemically inhibited using MPTP, a synthetic opioid. Instead of exhibiting the expected Parkinson’s-like behaviors, the mice still had what appeared to be normal motor function. Only after the norepinephrine receptors were then chemically inhibited did the mice show the “poverty of movement” (extreme slowness and stiffness) also seen in people with Parkinson’s disease.

More about norepinephrine: norepinephrine and adrenaline are structurally related. In the blood stream, norepinephrine, a neurotransmitter, is released continuously from certain nerves at low levels to maintain blood pressure, among other jobs. Adrenaline, the “fight or flight chemical,” is released from the adrenal glands, right next to the kidneys, during times of stress. Adrenaline increases heart rate and opens the bronchia (windpipes). Norepinephrine in the body maintains blood pressure. In the brain, norepinephrine increases alertness and wariness, sharply focuses attention, and can increase restlessness and anxiety: attributes of the medically recognized Parkinson’s personality.

Neurotransmitters do not easily cross the selective, semi-permeable membrane known as the blood-brain barrier. The body supply and the brain supply of neurotransmitters are kept apart unless the bloodstream levels are extremely, unnaturally high, or there is a health problem affecting the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. Brain-based norepinephrine and dopamine are produced and used in the brain. Blood-based norepinephrine and dopamine are produced and used throughout the body, and are kept out of the brain by the blood-brain barrier.

5. “Personality traits and brain dopaminergic function in Parkinson’s disease”; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 98:13272-7; Valtteri Kaasinen, MD, PhD et al; 2001. This 2001 study, published in one of the most respected journals in American science, describes the utterly unexpected discovery that people with Parkinson’s have elevated levels of dopamine activity in the brain’s anterior cingulate area, an area that manages risk assessment.

6. Here’s an example of what I mean by “garbled language,” followed by my translation using a more contemporary English. “Change of colors corresponds to pulses of the four seasons, which is valued by gods because it is in tune with the divine being and which enables us to flee from death and stay close [cling] to life.” That’s from the Su Wen, chapter 13-9, from A Complete Translation of the Yellow Emperor’s Classics of Internal Medicine and the Difficult Classic; Henry C. Lu, PhD; published by the International College of Traditional Chinese Medicine; Vancouver, BC, Canada; 2004; p. 116.

The word “colors” in the above quote is a very loose – and incorrect – translation from the Chinese characters for Se Mai, literally “pathways of light” or “currents of energy derived from lightwaves,” or “energy from light waves” (electricity) and is a reference to channel qi, but is often incompletely translated into English simply as “colors.”

The word translated as “pulses” in the above can also mean “rhythms” or “patterns.” The word translated here as “seasons” is usually translated as “phases.” However if preceded by the number four, it is often a reference to “the four seasons.” In our case, it’s a reference to the four neurological phases, or modes. The translator clearly doesn’t know that.

A quick translation into medical English would read, “Changes in the electrical paths of the channel qi correspond to the physiological behaviors of the four modes. The first mode, parasympathetic, is ‘in tune with the Divine being’ [joy and ease]. The second, sympathetic, enables us to ‘flee from death’ [fight or flight]. [The third mode is not listed in this sentence, but it corresponds to sleep mode.] The fourth, pause mode, allows one to ‘cling to life’ while hovering on the edge of death.”

The English- and Chinese-speaking practitioners of Chinese medicine that I’ve spoken to have had no idea that this section of the Huang Ti Nei Jing is discussing neurological modes because, since the mid-twentieth century, channel theory is no longer taught in schools of Chinese medicine. Current students and scholars alike no longer have a basis for translating this section. They have usually guessed that this sentence from the thousand-plus-years old medical tome is a random interjection about natural history, something along the lines of “Plants change color during the course of the four seasons.”

The rest of the chapter that follows this introductory sentence makes no medical sense if this chapter is about leaves changing colors in the fall. The rest of the chapter makes stunning good sense if one recognizes from hands-on experience that the channel qi does flow differently in each of the four neurological modes.

Since the communist revolution in China, channel qi is regarded as an historical superstition, similar to religion and classical references to the Divine. Teaching channel qi as a medical reality has been illegal in China for more than half a century. You could be jailed for it: “sent to camp.” For this reason, most acupucturists today are not taught about channel qi or how to feel it: the original essence of this field of medicine. This ban has led to some truly bizarre translations of the old medical books into modern, atheistic Chinese and thence into English. The political reasons for this legal ban are discussed in depth in some of my other books, including Hacking Chinese Medicine and Tracking the Dragon.

As with much of the classical Chinese literature, one needs to already know what is being discussed in order for the cryptic, terse language to be intelligible. The ancient medical writings were never meant as explicit guides for the general public. Rather, they were insider, very often metaphorical, references to a primarily oral, closely guarded tradition.

The modern English term “meridians” is sometimes used in place of the word “channels.” The word “meridians” means “imaginary lines”: lines used as a construct to help organize information. The channels are not imaginary. However, the use of the word meridian is in line with the modern Chinese political stance that channels do not actually exist.